This post is a reply to David Didau (@LearningSpy) – Squaring the Circle: Can Learning Be Easy and Hard? I urge you to read it because it poses a very good question and he brings, as always, a lot of research to discuss this issue.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Bjork’s work, that I introduced you to a year or two ago, tends to take over the educational debate, as Willingham’s work does. Excessive cognitivism (or any other theory of learning) obstructs the bigger picture of learning because it focuses on a limited set of variables or just one in some cases – either internal (e.g. memory), relational (e.g. social learning), emotional, you name them.

Some points.

If performance (what the student does – writes an essay, draws a rectangular prism etc.) is a poor proxy for “learning” (Bjork), then it is quite difficult to *infer* the “learning“ that takes place (learning being an internal mechanism/process). Note that we cannot pinpoint with precision what the student “learned”: we can only deduce based on – surprise – performance. It follows then that we can only use this vehicle (performance) to assess student “learning”. Which gets me to the next question: what is learning then and how do you know?

That is where Bjork’s work and CLT (Cognitive Load Theory – that I knew of years ago, too) become problematic to me – not to mention CLT was questioned, too, back in 2009 – conceptual and methodological flaws. This entire research gravitates around memory storage and retrieval. Surely, memory is “the residue of thought” but the implications for teaching (according to Bjork) are testing, interleaved practice and so forth. Basically, teachers = memory trainers.

That is why I confront Bjork’s term “learning” with Wiggins’s “understanding”. Even in the case of “experts” they do not simply *train* their memory. “Practice” in their case is not exclusively memorization – unless you will use again the bad analogy of expert chess players – such a narrow, tool-determined type of learning. The chess analogy is an extremely poor one for various reasons but two are obvious: first, chess players have a single tool to work with (a chessboard), secondly, there is a *convergent* type of thinking employed (geared towards checkmate). Experts in any other domain are involved in ill-structured type of problems, with more variables, that require a divergent type of thinking – new solutions to the climate change for instance, demographic challenges, effects of drugs on different populations etc. Even the annoying analogy with sports/coaching is wrong – coaches deal with more than mere memory – new players, new team dynamics, new field to play on, new strategies depending on the opponent etc. Even a student working on math problems will encounter increasingly difficult tasks that require more than “memorizing” (unlike chess players).

What we aim in education, therefore, is not mere memory storage and strength – we use memory but this is not the final scope. We aim for understanding and surpassing the apparent “isolated” facts to converge into greater mental constructions. Also,”learning” takes place not only through memorization and testing – it involves questioning, problem-solving, discussions, open-ended tasks, self-directed research. And, before you apply the label of “progressivism”, do think of your own learning and ask yourself if these three examples above did not push your learning. Thus, Willingham’s somewhat constrained idea that the brain “is not designed for thinking” falls short. As Solocontrutti noted, “Then you would have to wonder what it is designed for. It is the only organ we *have* for thinking.”

As far as expert vs. novices topic is concerned, if you read the 2014 issue Applying Science of Learning to Education (where Hattie, Willingham, Bjork, Sweller are referenced to or contribute chapters), the idea of “expertise” is not solely reserved for *adult* experts. “Experts” are also considered more knowledgeable students and the “expertise reversal effect” is mentioned –

“ An instructional technique that reduces working memory load for low-knowledge learners (e.g. by providing strong instructional support) might lose its relative effectiveness and may even bring negative consequences for more knowledgeable learners (expertise reversal effect).” (p. 32)

“More knowledgeable learners may learn better in an environment without guidance. Studying worked examples may require experts to cross-reference external support materials with already learned procedures. Learners could therefore be distracted from fluent cognitive processing by taking full advantage of their existing knowledge structures and could have working memory overloaded by additional, extraneous activities. From this perspective, the expertise reversal effect can be understood as a form of the redundancy effect. It occurs by co-referencing the learners’ internal available knowledge structures with redundant, external forms of support. “(p.35) “Knowledgeable” thus becomes a point in a continuum within a topic – one student who already knows a lot about, say, two-digit addition, will find two-digit addition drills completely unhelpful – move her/him to open-ended problems where two-digit addition *and* other math concepts are involved.

NOTE: The same student can be at different points on this continuum in time – it is not *only* age-related. But also different students – hence the need for differentiation that is, again, downplayed by “traditional” teachers. I had students at the beginning of the school year whose level of English language (and knowledge of math, geography, history etc.) varied greatly – students who had one English-speaking parent, students who had both parents speakers of English, students who were juggling 4 languages (father – Swedish, mother – Serbian, academic language in school – English, second language of instruction – Italian), students who were in their 1st, 2nd or 3rd year of English. Not to differentiate learning for this extremely varied array of knowledge and skills would be simply ridiculous – I would have inevitably failed many of them.

Another point: you mention only “difficulty” as a way to make learning stick. That is only one answer. Complexity is another – but I talked about it on Twitter quite a lot so I won’t return to it. If you were to apply this to a curricular endeavor that would mean not only difficulty *within* the subject but also complexity achieved*across* disciplines (transdiciplinary learning). I can give you two examples of each from my own teaching (grade 2, second-language learners).

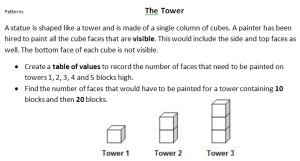

a) Within-subject: Patterns

DIFFICULTY: increasingly difficult pattern recognition (see examples -click, it will enlarge)

COMPLEXITY: pattern recognition + other mathematical concepts (number facts, number strings, data etc.) * see open-ended problem, point c)

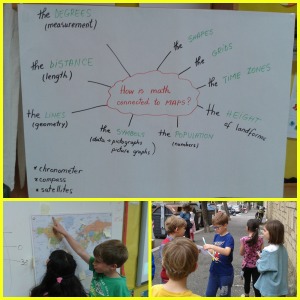

b) Across subjects: Orientation and maps)

Geography: understanding maps (bird eye view, floor plan, map key, latitude and longitude, compass rose etc.)

History: history of explorations (explorers, routes etc.)

Math: turning a 3D shape (“Earth”) into a 2D print (map), grid coordinates (battleship game, gridlock game)

Social Studies: politics vs. science (Eurocentrism, why most maps are drawn the way they are).

Literacy: writing an explorer’s diary, creating a class “science” magazine

All using questioning, problem-solving, surveys, walks (and mapping the school surroundings), online tools and so forth.

Why this effort to building a strong “conceptual” understanding, so downplayed or questioned by “traditional” educators? Because of the “generation effect” also mentioned in the research (chapter Generating Active Learning, p. 71):

“In the field of psychology, one way these concepts are described and tested is as an experimental finding called the generation effect or generation advantage. In its simplest form, the generation effect is the finding that, in most cases, information is more likely to be remembered when it was studied under conditions that required learners to produce (or generate) some or all of the material themselves, versus reading what others had prepared.”

Does this mean memory played no role whatsoever? Not at all and you should know that I am a fervent promoter of knowledge, practice, quality teaching and learning, of research . The students had to read a lot, to write about their learning, to explain their thinking, to connect pieces of information, to analyze, to synthesize and so forth.

I guess it all comes down to the vision and values in education you uphold, and use research findings to support them and guide your instruction.